The Top 5 Skills I Learned From The University of Toronto Self-Driving Cars Specialization (2023)

Autonomoose — The University of Toronto-Waterloo self-driving car research platform (source: link).

I recently completed the Self-Driving Cars Specialization from the University of Toronto on Coursera, and in this article, I’ll highlight the top 5 skills I’ve acquired during this course. But, before diving into that, let me give you the reasons that propelled me to enroll in this program.

- A child’s dream

My passion for cars has been burning brightly since I was a child. My father was a mechanic, and I used to help him in his garage performing some basic tasks such as checking the oil and changing tires. His love for cars and driving inspired me to pursue a career in the automotive industry.

- Market Growth

I’ve been working for over 5 years now as a software engineer. As the industry pivots to sustainable and data-driven technologies, car brands and OEMs are harnessing high-quality data to create more futuristic transportation. This leads to a growing demand for software engineers specializing in self-driving cars. As a result, market forecasting suggests that by 2030, up to 15% of new car sales could be fully autonomous, generating $300–400 billion in revenue by 2035.

- The potential to save thousands of lives

A 2015 study conducted by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) revealed that human error was responsible for over 94% of road accidents. A recent projection for 2022 traffic fatalities estimated that 42,795 people died in car crashes in the US and 20,600 in Europe. Self-driving cars have the potential to reduce these fatalities and make driving safer, more enjoyable, inclusive, and sustainable.

- Canada: The “Motherland” of AI

Finally, I took this course from the University of Toronto (U of T) due to its prominent reputation in the AI field. U of T is home to some of the world’s leading AI experts, including the 2018 ACM Turing Award Laureates, Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun, and Yoshua Bengio, who are often referred to as “the godfathers of AI”. But also, the new wave of AI pioneers such as Ilya Sutskever, from OpenAI and Aidan Gomez, from Cohere, who co-wrote the Transformers paper that led to the birth of Large Language Models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s GPT models, among others.

Course Overview

Structure and Contents

The specialization consists of 4 modules, each with video lectures, quizzes, and assignments. However, to ensure a comprehensive understanding and alignment with common self-driving car architectures in today’s industry, I have restructured the courses into 5 modules:

- Introduction to Self-Driving Cars (‘The Fundamentals’): gives a comprehensive overview of the state-of-the-art in the autonomous driving industry. It includes a brief history, terminology clarifications, design considerations, safety assessment, as well as the challenges and future of the technology.

- State Estimation and Localization: teaches topics such as sensors for localization, state estimation methods, sensor fusion, and Kalman filters.

- Environment Perception: covers how to identify and track objects in the environment using cameras and LiDAR, as well as how to segment objects and create 3D models of the world.

- Motion Planning: teaches how to plan safe and efficient paths for self-driving cars, and how to deal with uncertainty and unexpected events

- Control: covers how to control the actuators of a self-driving car, such as the steering wheel, brakes, and accelerator. As well as how to deal with disturbances and optimize the control system.

Prerequisites

Building a self-driving car is a complex task that requires expertise across multiple fields, including computer science, linear algebra, statistics, physics, and robotics. Familiarity with simulation tools such as Carla Simulator is also beneficial.

Notes: I curated this awesome list, where you can find all the prerequisites for the course.

Instructors and community forum

The instructors are Professor Steven Waslander and Jonathan Kelly, who have over 30 years of experience in engineering and autonomous robotics research. Industry experts from leading companies such as Zoox and Oxbotica provide real-world insights during the courses. Learners can also join a forum to ask questions and interact with instructors and peers worldwide.

Here are the top 5 skills I’ve learned from this specialization.

1. How to Build a Self-Driving Car at Scale

Driving is a challenging task that requires us to sense the world around us and make difficult decisions while navigating a complex environment. Humans are not perfect drivers, and as a result, 1.3 million people die in road traffic crashes each year. Self-driving cars have the potential to reduce these fatalities, but they must outperform humans in every aspect of driving. Building such a system is therefore a complex challenge that must be addressed carefully.

The first stage of the self-driving car design is to define an Operational Design Domain (ODD). The ODD specifies the conditions and environments in which the car is designed to operate. Based on the ODD, we can define three types of driving dynamic tasks (DDTs):

- Operational driving: The car’s ability to control its motion, such as steering, braking, and accelerating.

- Tactical driving: The car’s ability to detect objects and events that immediately affect the driving task and to react to them appropriately. This is also known as object and event detection and response (OEDR).

- Strategical driving: the car’s ability to plan how to get from point A to point B and make decisions accordingly.

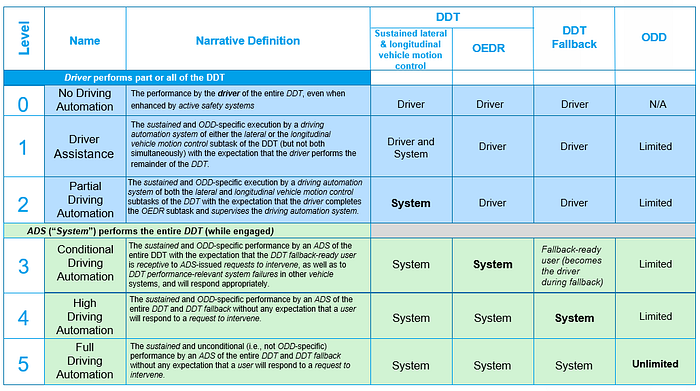

In today’s industry, we use the SAE J3016 standard to classify the DDTs in terms of driving automation levels.

SAE J3016 — the level of driving automation. (source: link)

The SAE J3016 standard defines six levels of driving automation, from Level 0 (no driving automation) to Level 5 (full driving automation). The progression moves gradually from driver-assistance features to automated driving features. This allows us to establish the specific roles of the system and the driver in performing the DDT.

The next step is to define the software and hardware components that are needed to meet the automation requirements. These components must comply with safety standards and regulations of the geographic area where the vehicle will operate.

- Self-driving car hardware architecture

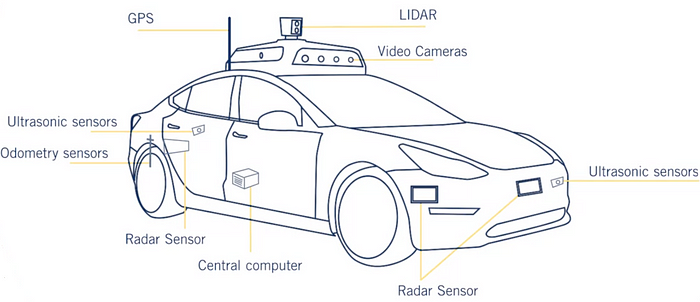

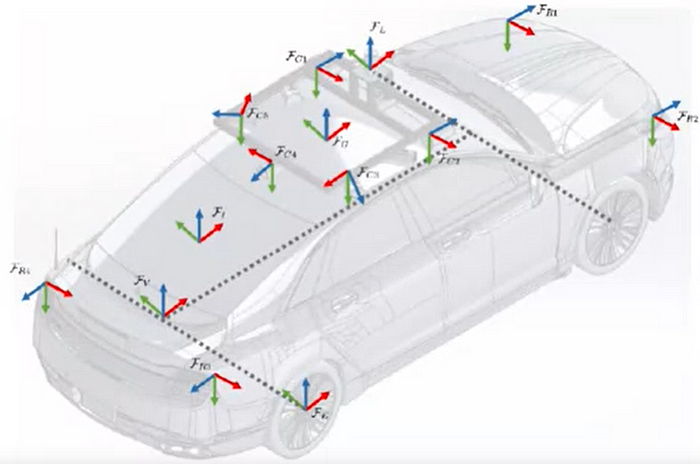

Self-driving car hardware components. (Source: link)

A basic self-driving car hardware architecture consists of various sensors collecting environmental and vehicle data, and a central computer. These are two categories of sensors: exteroceptive, which captures surroundings (cameras, lidar, radar, and ultrasonic sensors), and proprioceptive, which tracks the vehicle itself (IMUs, GNSS/GPS, and wheel odometry).

The central computer is the “brain” of the self-driving car. It is responsible for processing the data from sensors and making driving decisions. Notable computing systems include NVIDIA DRIVE PX/AGX and Intel & Mobileye EyeQ. Some brands, like Waymo and Tesla, develop their unique hardware computer, while others rely on AI chip suppliers like Nvidia, Intel, and AMD, among others.

- Design a scalable software stack

There are currently two software architectures commonly used in the autonomous industry: Modular and End-to-End approaches. Vehicle brands choose their approach based on their needs and resources. For example, Waymo uses a modular approach, whereas Tesla uses an End-to-End one, relying only on cameras and a single neural network.

The specialization focuses on modular software stacks, which are more flexible and cheaper to scale for large and complex projects.

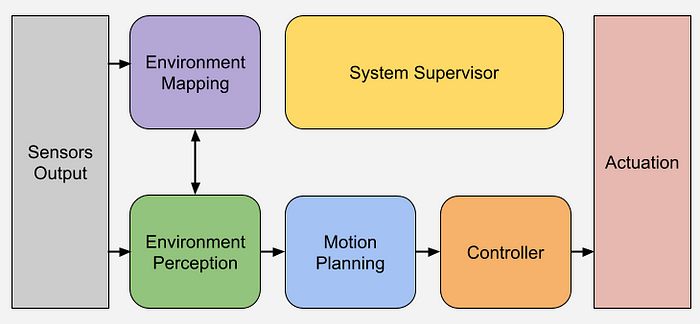

Self-driving car software architecture (Source: link)

The 5 core modules of the software stack are:

- Environment mapping: maps objects around the vehicle for collision avoidance, ego-motion tracking, and planning.

- Visual perception: identifies location and relevant environment elements for driving tasks.

- Motion planning: decides actions based on perception and mapping data.

- Controller: adjusts steering, throttle, brake, and gear settings to follow the planned path.

- System supervisor: monitors the car and warns of subsystem failure.

Note: for additional insights, refer to Course I, Chapter 2 notes on my GitHub.

- Build a safety assessment strategy for self-driving cars.

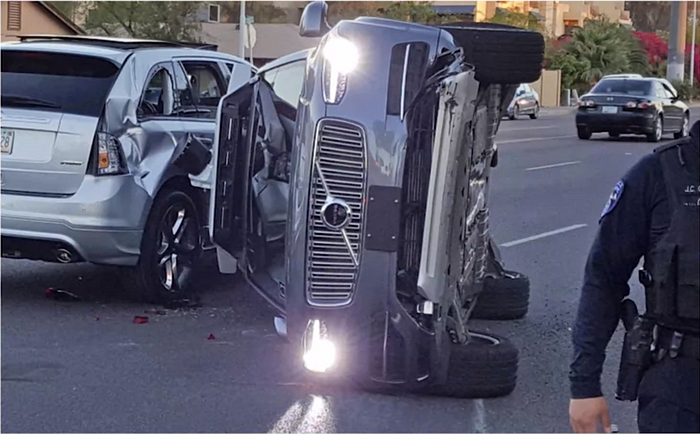

Uber Self-Driving Car Crash in 2017 (Source: link)

Vehicle safety has been a top priority in the automotive industry, with continuous advancements in safety technology, from seatbelts and airbags to advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS). The self-driving car is the result of years of research and innovation in vehicle and road safety.

“Self-driving cars are the natural extension of active safety and obviously something we should do.” — Elon Musk

The specialization covers some of the common safety frameworks for self-driving cars. These include ISO 26262-ASIL, ISO/PAS 21448-SOTIF, FMEA, fault tree analysis, and HAZOP. The specialization also covers how vehicle brands are using these frameworks to analyze specific scenarios and hazards during and after self-driving car deployment.

Note: For additional insights, refer to Course I, Chapter 3 notes on my GitHub.

In 2017 the NHTSA suggested a safety policy framework to support entities (brands and stakeholders) in the development, testing, and deployment of automated driving systems (ADS) of Levels 3–5. The framework describes 12 rules split into three classes: a system engineering approach to safety, autonomy design, and testing and crash mitigation.

The NHTSA encourages these entities to provide voluntary safety self-assessment (VSSA) disclosures to the public to show how they are addressing safety. Many companies in the industry including Waymo, Zoox, Apple, GM, and Ford, among others have shared their safety policies and strategies. You can find their VSSA Disclosures here.

2. How self-driving car sees the world and understands its environment

The self-driving car uses a set of sensors including Cameras, LiDAR, and Radar to perceive and understand its surroundings. The perception module takes the raw sensor measurements and performs two important tasks:

- Localizing the ego-vehicle in space. This means determining the car’s position, orientation, and velocity.

- Classifying and locating the important elements of the environment. This includes other vehicles, pedestrians, cyclists, and objects such as traffic signs and lights.

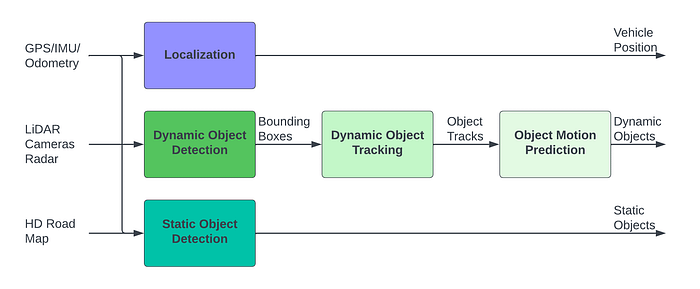

Self-Driving Car Perception Pipeline

Self-Driving Car Perception Pipeline. (Source: link)

The three core components of the Perception stack are:

- Localization, which takes the information from GPS, Inertial Measurements Unit (IMU), and wheel odometry sensors to output the vehicle’s location and orientation in space.

- Dynamic object detection, which uses camera and LIDAR data to create 3D bounding boxes of dynamic objects, such as other vehicles, pedestrians, and cyclists. It also tracks these objects over time and predicts their future path.

- Static object detection, which takes camera and LiDAR data to locate important elements in the scene such as lanes, road signs, and traffic lights.

Building a reliable perception stack is crucial for a self-driving car, just as eyes are important for human drivers to see the world. The specialization covers state-of-the-art methods used to build each of these components of the perception stack, including 3D computer vision, visual features, FeedForward, Convolution Neural Networks, 2D object detection, and Semantic segmentation.

Note: For additional insights, refer to Course 3 notes on my GitHub.

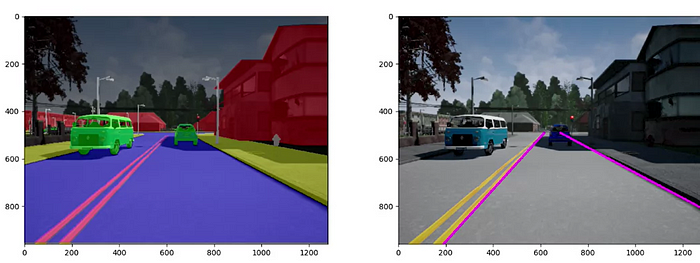

At the end of this module, I was able to apply these skills to build a basic self-driving car perception stack in Carla Simulator. The system uses camera data to estimate 3D drivable space, performs lane estimation, and 2D object detection to avoid obstacles in the road.

Left Image: Semantic segmentation of the scene. Right image: Lane detection of legal drivable space

The system takes as input semantic segmentation output from the SegNet model outputs lane detection and performs obstacle avoidance.

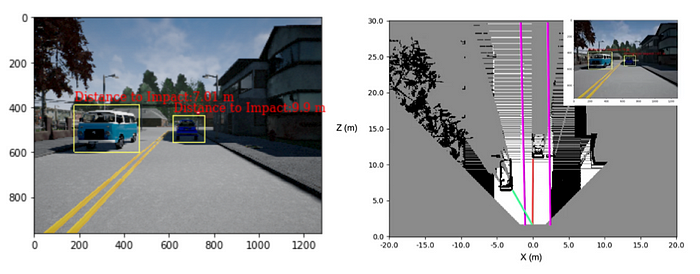

Obstacle detection and 3D bird view of the scene, where the pink lines represent legal drivable space. The red lines represent the safety distance with the vehicle in front. The green line represents

If you want to find out more about this project, chekout this GitHub repository.

The perception stack suggested in the specialization is cheap to scale. Therefore, the solutions used in this project could be extended to meet the requirements of even more complex applications

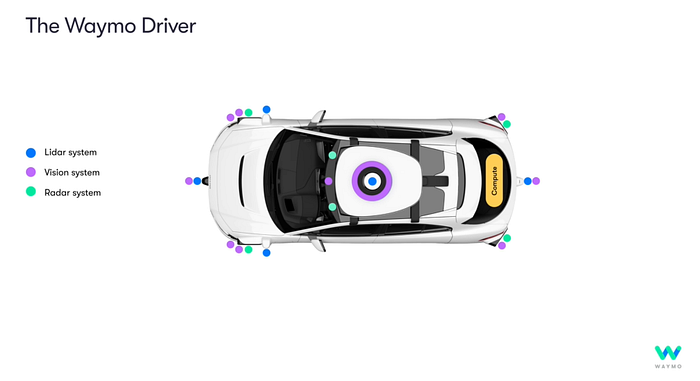

The Waymo Driver perception sensors configuration. (Image credit: Waymo Team)

For example, the Waymo Driver uses a suite of cameras, lidar, and radar sensors to get a complete understanding of its environment. It then relies on sensor fusion to enhance the benefits of each sensor. For example, the lidar provides 3D depth information and object detection, the camera captures visual appearance, and the radar is used in poor weather conditions, and to track moving objects.

3. How self-driving car figures out where it is in the world

Self-Driving Car Localization (Source: link)

In order to navigate safely and accurately in the world, a self-driving car must know its position. This is done by performing localization and mapping. The car uses a variety of sensors, such as inertial measurement units (IMUs), global positioning systems (GPS), and wheel odometry to produce accurate vehicle positioning. Some localization modules also use LIDAR and camera data for higher precision.

The raw sensor measurements can be noisy due to sensor imperfections, so it is crucial to eliminate these errors to get the accurate vehicle’s location and motion. State estimation is the process of determining the most likely value of some of those measurements. Vehicle localization relies on the map of the environment where the car will drive.

The Self-Driving Car Localization and Mapping Pipeline

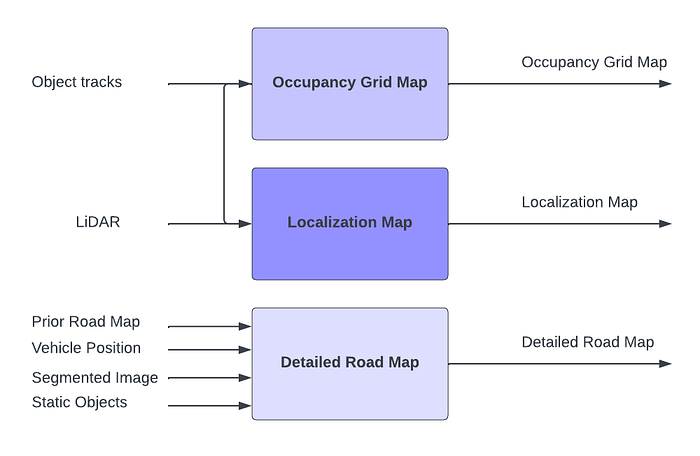

The Self-Driving Car Localization and Mapping Pipeline (source: link)

The three core modules for mapping environment module covered in the specialization are:

- The occupancy grid map, constructed mainly from LIDAR data, portrays static objects in grid cells with occupancy probabilities, accommodating uncertainty.

- The localization map, derived from LIDAR or camera data, refines ego state estimation.

- The detailed road map, offers road segment information for motion planning, such as lane marking and signs, combining pre-recorded and real-time data.

Environment mapping and localization are vital parts of the self-driving car stack since they enable the car to have a globally consistent representation of the world. The specialization covers a wide range of methods and algorithms to build each module of the mapping and localization pipeline. These include state estimation methods (least square, linear and nonlinear Kalman filters), sensor fusion, typical vehicle localization sensor models (GPS, IMU, and LiDAR), LiDAR scan matching, and ICP algorithms.

Note: For additional insights, refer to Course 2 notes on my GitHub.

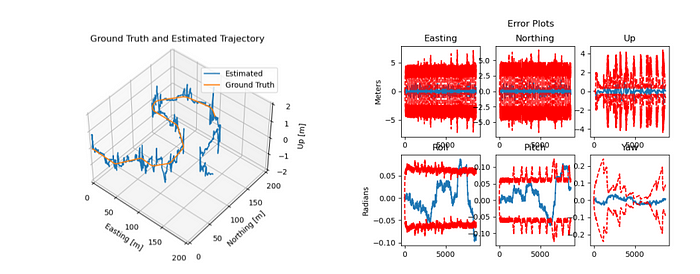

Based on the tools I learned from the specialization, I was able to build a filter-based self-driving car state estimator to determine the vehicle’s position and orientation on the roadway. The system takes a variety of data streams from Lidar, IMU, and GNSS and performs the following tasks:

- Taks 1: performs the filter prediction step and the correction step

- Task 2: handles the effects of sensor miscalibration on the vehicle pose estimates.

- Task 3: implication of sensor dropout. Examine the drift and the uncertainty in the position estimate changes when sensor measurements are unavailable.

Here is the output for Task 1.

From left to right: Ground Truth and trajectory estimate. And the estimator error (blue) and uncertainty bounds (red).

Interestingly, we can see that the estimator output is quite accurate relative to the Ground Truth. On the other hand, the estimator error (blue plot) remains within the uncertainty bounds (red plot), which gives an indication of how well the model fits the actual dynamics of the vehicle, and how well the estimator is performing overall.

If you are interested in finding more, check out the entire project on my GitHub.

4. How self-driving car decides to navigate the world safely

Credit Image — Waymo Team (Source: link)

To navigate the world safely, a self-driving car must deal with multiple scenarios in a complex environment. This includes other vehicles, pedestrians, cyclists, and static objects on the road. The car must also obey traffic laws. Motion planning is the process of finding a safe and efficient path for the car to follow.

The motion planning module gets information from the environment mapping and perception components, such as the vehicle’s position, a detailed map, and an occupancy grid. It then predicts the future state of the environment, creates the best trajectory path, and generates the velocity profile for the control stack.

Self-Driving Car Motion Planning Pipeline

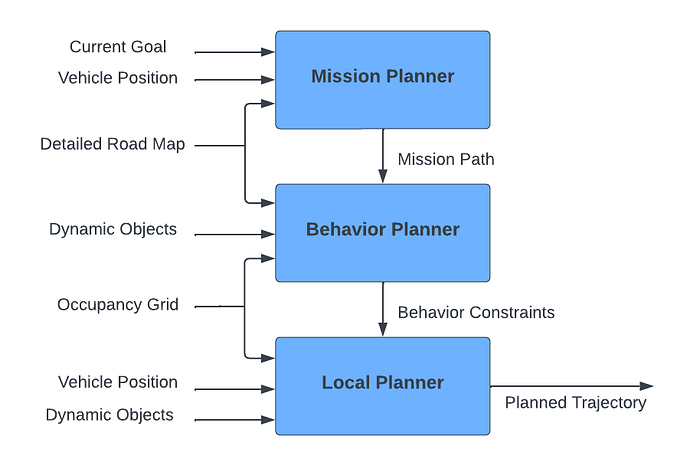

Building an accurate motion planning stack is so challenging that it often requires decomposing the problem into 3 layers of abstraction as follows:

Self-Driving Car Motion Planning Pipeline. (Source: link)

- Mission Planner: focuses on long-term planning. It computes the optimal path for the self-driving car from its current position to a given destination. It takes into account factors such as the car’s starting and ending points, the desired speed, and the traffic conditions.

- Behavior Planner: handles short-term decisions by generating safe maneuvers for the mission path. This includes choices like merging lanes based on desired speed and nearby vehicles’ behavior, along with associated road constraints.

- Local Planner: takes data from behavior planning, the occupancy grid, vehicle limits, and dynamic objects and continuously generates smooth and safe path trajectories that the car can follow.

Although autonomous motion planning is a very active research field, evolving rapidly, the specialization covers state-of-the-art methods and algorithms to build an effective motion planning stack. Some of the topics covered include:

- Mission planner algorithms, such as Dijkstra and A-star (A*). 2D occupancy grid generation.

- Behavioural Planner concepts, like Finite State Machines(FSM), rule-based systems, Machine Learning-based: reinforcement learning, and end-to-end learning. But also, motion prediction and collision-checking methods.

- Local planner methods for path planning: sampling-based, variational, lattice planner, path optimization, and velocity profile generation.

Note: For additional insights, refer to Course-4 notes on my GitHub.

Using the skills I gained from the specialization, I built a self-driving car motion planner stack that can handle real-world scenarios encountered by autonomous vehicles every day. The system takes a planned map in the Carla Simulator and navigates safely and collision-free to the final goal.

The planner receives a set of waypoints in a given road network on Carla Simulator, and avoids static and dynamic obstacles while tracking the center line of a lane, and while also handling stop signs.

If you are interested in finding more about this project, check out this GitHub repo.

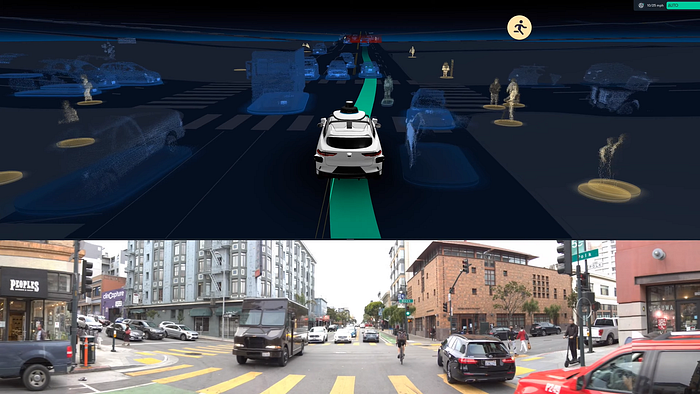

This planning stack can serve as a foundation for a more intricate project and can be gradually adjusted to meet additional requirements. For example, Waymo uses a rule-based motion planner combined with machine learning and reinforcement learning for their self-driving car, The Waymo Driver.

Waymo Driver navigating around San Francisco, California. (Image credit: Waymo Team)

5. How self-driving car applies the driving commands to move through the world

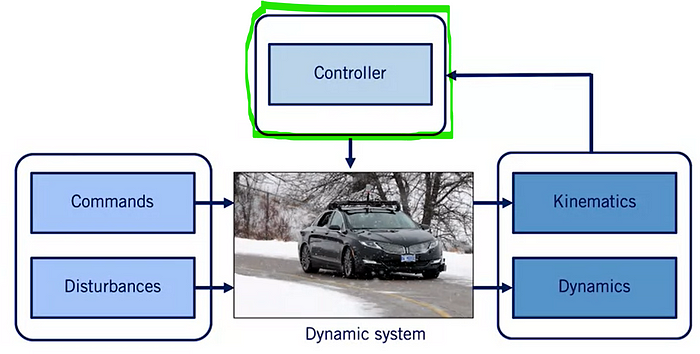

Self-driving car controller (source: link)

In order for a self-driving car to move safely through the world, it needs to apply driving commands to actuators, such as braking and throttle to move forward and steering commands to turn left and right. The vehicle controller executes the planned path trajectory generated by the motion planner to get the self-driving car to the destination goal while complying with speed constraints and road regulations.

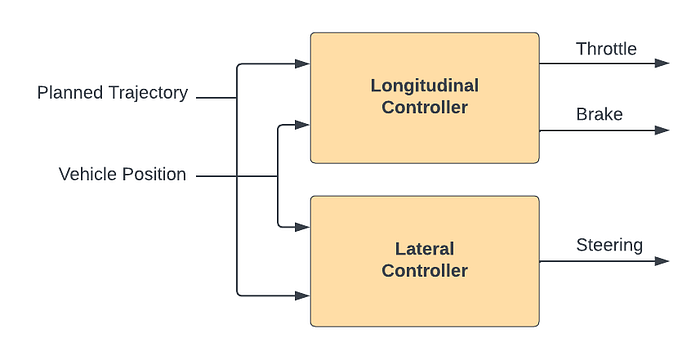

The vehicle controller decomposes the control problem into longitudinal and lateral control.

Self-driving car controller pipeline. (Source: link)

- The longitudinal controller regulates the throttle, gears, and braking system to achieve the correct velocity.

- The lateral controller outputs the steering angle required to maintain the planned trajectory.

Both controllers calculate current errors, track the performance of the local plan, and adjust the existing actuation commands to minimize the errors going forward. One of the biggest challenges in the field is to find the “perfect” controller that can minimize these errors close to zero.

There are many types of controllers used in the driving industry today. For longitudinal control two types of controllers are covered: Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID), the Feed Forward, and the feedback controller. For Laterall controller: Geometric controllers such as Pure pursuit (carrot following), Stanley, and Model Predictive Controller (MPC).

Note: For additional insights, refer to the Course I, Module 5 & 6 on my GitHub.

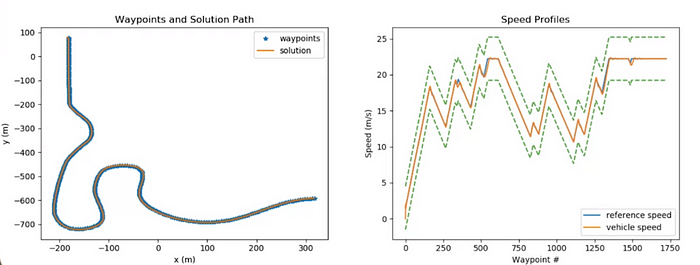

Using the skills I gained, I built a real-world self-driving car controller in the Carla simulator. The system follows waypoints and navigates safely and efficiently along the racetrack. The controller receives a sorted list of waypoints, which are evenly spaced along the track. The waypoints are the reference signals, which include the vehicle’s desired position and speed.

Path trajectory of waypoints where the vehicle navigates.

For longitudinal control, I implemented the PID Controller, which takes the desired speed as the reference and outputs throttle and break. While, for lateral control, I used the Stanley controller which takes the waypoints and outputs the steering. Combining both the longitudinal and lateral controllers produces the following speed profile and trajectory.

On the left: Waypoints and vehicle trajectory. On the right: vehicle speeds(orange) compared to the desired speeds(blue), bounds thresholds (green).

The controller tracks the reference speed well and follows the path with very little error.

If you are interested in finding more, check out the entire project on my GitHub.

Conclusion

I particularly enjoyed the hands-on projects, which helped me develop my skills in autonomous driving and gain practical experience. Despite being fully built on the Carla simulator, the projects are based on real-life data tested on Autonomoose (U of T-Waterloo self-driving car platform).

As Zoox CTO Jesse Levinson said, “If You Can’t Simulate it, You Can’t Make it.” Simulators allow engineers to test complex scenarios with multiple agents in different variations, including dangerous situations that would be too risky to try on real roads. We can then transfer the knowledge learned in the simulation into the real world by doing some fine-tuning.

On the other hand, I found it would be helpful to have a coverage of C++ in the specialization, given that over 95% of embedded systems code is in C/C++. Additionally, some hands-on exercises on how to build and apply deep learning models to perception and motion planning problems could also be beneficial.

After completing this specialization, I am convinced that self-driving cars will revolutionize transportation and make the world a safer place, and I am eager to take part in this exciting mission.

References

[1] Self-Driving Cars Specializations — Coursera

[2] Self-Driving Cars Specialization — GitHub Notes & Assignments

[3] Self-Driving Cars Specialization — Full projects (You may want to check this out! )

[4] Car Crash Deaths and Rates

[5] Automotive revolution — perspective towards 2030, McKinsey & Company

[6] Udacity vs. Coursera: Which Has the Better Self-Driving Cars Program? (2022)